The internet and the powerful social media platforms now host among the worst forms of violence against journalists and are a rising threat to media freedom. Women journalists come in for particular targeting in a trend now called cyber-misogyny. Naming it makes it no less painful, as I have found.

Every morning, I pick up my phone and check WhatsApp messages. Then, I open my Twitter feed. “Bitch!” reads a response to something I’ve posted or written or reported. I block. “Cunt,” reads another. Block. “Racist, go back home,” says another.

“I will smack you so hard, you won’t know your name,” I type. And then block.

Online abuse has become so commonplace that taking it in and blocking is part of the daily routine now. Just occasionally, you have to fight back.

When Donald Trump told four US congresswomen to go back to where they came from a few weeks ago, igniting a fusillade of stories from people who had been told so, I thought about writing on the black digital Trumps in South Africa. “Go home” and “Go back to India if you don’t like it here,” are quite regular taunts on Twitter. As Raymond Suttner has written here, this othering of people delegitimises them, to create hate.

Then, my former colleague (and a friend, I thought) Piet Rampedi in July started his infamous thread numbering and naming a group of journalists he called the “Cabal” who are, by his judgment, part of a narrative of disinformation — himself deliberately misleading the public.

I was number 29. I muted Piet on Twitter because the deluge of responses was too abusive to cope with, but it had real-life consequences.

The following Monday, after Piet’s List, at the Zondo Commission of Inquiry, I sat near the back in the crowd which accompanied former President Jacob Zuma to give testimony. During tea-time, somebody started stage-whispering “cabal” then someone else picked it up “cabal” and then another “cabal”. Then they laughed. It stuck to me like spat venom. I’m still not sure I did quality journalism that week because I kept mulling Piet’s tweet and hearing “cabal”, “cabal”, “cabal”. I’ve worked hard for 29 years as a journalist to not be part of any cabal, so the whispers cut to the heart of me.

The Internet and violence against journalism

The Internet and the powerful social media platforms now host among the worst forms of violence against journalists and they are recognised by the United Nations agency which deals with free media, Unesco, and other global free media advocates as a rising threat to media freedom. Women journalists come in for particular targeting in a trend now called cyber-misogyny. Naming it makes it no less painful, as I have found.

As I reflected, I realise that when reporting, I walk with a stoop now, bent from the world as if to protect myself. It’s not like me. At news events, like EFF media conferences, I make myself small and will ask questions in a way that sounds to me, as I reflect, almost obsequious. It’s definitely not like me. I chose not to be a named as part of this week’s Sanef, the national editors’ forum, the case against the EFF not because I don’t identify with it or support it with my full heart. I want the spotlight to turn away because the insults sear at me. I told a friend the other day that I have begun to imbibe the insults and opprobrium, to cut my cloth to fit the words flung with abandon and to begin to second-guess myself.

Julius Malema’s affidavit

So, it was with some disbelief that I read EFF President Julius Malema’s responding affidavit in the hate case speech, underway this week. Sanef is bringing a case in the Equality Court against the party to have journalists declared a group which requires protection under Section 10 of the Constitution which governs hate speech.

In the affidavit, I get a high-five from Malema for not being a named journalist in the court case (with Ranjeni Munusamy, Pauli van Wyk, Adriaan Basson, Barry Bateman and Max du Preez). Then, I get an additional shout-out for still going to EFF press conferences (some of my colleagues won’t go because it’s a risk) and for “engaging as an equal”, according to Malema’s affidavit.

I am no equal. I am a roadkill. The case revolves around Malema’s speech outside the Zondo Commission of Inquiry into State Capture in November 2018 when he outdid even himself in the rhetoric of hate. In a wide-ranging speech that would come to define how the EFF positions itself in the era of State Capture 2.0, he took aim at Minister of Public Enterprises Pravin Gordhan, at the clean-up at the revenue service SARS, at the commission itself and then he named a “Ramaphosa Defence Force” as publisher Palesa Morudu, editor Max du Preez, activist academic Nomboniso Gasa (and her “husband”), legal scholar Pierre de Vos, journalist Ranjeni Munusamy and me. By my recollection, I was the only one of us at the EFF rally outside the commission that day and so got special treatment.

“Ferial with all her skills as a former editor why are you not asking Pravin if he has an account outside South Africa. Ferial never asks (these questions), instead, she attacks EFF.” Malema told his supporters to write down all our names and to “attend to them decisively everywhere you see them”.

It doesn’t get any clearer than that in the world of trolling armies; it was an instruction to attack, either online or even “IRW” (in the real world).

But then something happened that made Malema pull back.

The EFF crowd around me started growling, even in the face of at least two lines of police officers brought in to secure the precinct around the commission of inquiry. Malema looked over, saw what was happening and being the brilliant (perhaps Machiavellian) politician he is, he changed the tune.

“You must engage with them from a civilised point of view. You must never be violent with them.” He warned the crowd against harming the people he had named straight after telling them to “attend to them decisively”.

Now advocate Tembeka Ngcukaitobi for the EFF is using that change of tune to argue that political speech is often only rhetorical and that Malema cautioned his supporters. In addition, he argued on Monday 5 August 2019 that journalists cannot be given special protection in terms of Section 10 of the Constitution or it could open the floodgates for other groups, such as politicians, to claim similar treatment. This, he argued, would harm Section 16 of the Constitution which enshrines free expression.

It’s a clever argument and one that must resonate with journalists who, as advocate Danny Berger (SC) for Sanef said, are the troops of free expression and of free media. I don’t want to curtail free speech, but neither do I want to feel so permanently nervous.

‘I need that thing’

I’m not sure that the battle against online violence will be won in the courts; but I do know it will be won by the powerful social media platforms such as Twitter, Facebook, WhatsApp and Google doing more to prevent technology being weaponised in the way it has been.

In April, Malema took down a pinned tweet which in he had clipped a WhatsApp message from journalist Karima Brown, including her number, after Twitter told him to. At a press conference, he told journalists that he had done so because “I need that thing (Twitter)”.

Malema is a general and Twitter is his army of 2.4 million followers. He is not the first leader to use the social platform this way. Trolling armies are now used around the world by politicians to grow or protect or gain power.

In the Philippines, Rodrigo Duterte has used a Twitter army and his legal arsenal to hound the journalist and editor Maria Ressa and her site rappler.com. In India, journalist Rana Ayyub is a thorn in the side of Narendra Modi’s growing nationalist authoritarianism. She is trolled by a bot force of hundreds of thousands of Twitter accounts and by real-life supporters of Modi too.

The same thing is happening in Mexico, in Central America, in Vietnam, Ukraine, everywhere. Social media has made democracies more democratic by giving people a voice, by making sure the media is more accountable (and that it is not the only platform in town because every person with a smartphone or a data point is their own media), thereby smashing media monopolies.

But it also holds up the threat of practices dangerous enough to make the life of journalists so dangerous that they quit. Or it can result in the election of authoritarian regimes or political change so seismic that it turns the clock backwards. It is now commonplace that disinformation played a large part in the Brexit referendum to split the United Kingdom from Europe; and that a disinformation campaign by Cambridge Analytica, the company which scraped and sold Facebook data, may have been a significant factor in delivering the era of US President Donald Trump.

Twitter can hurt that way

Ten years ago, the title I edited, City Press, published an art review, one of the images of which was a painting by the artist Brett Murray who is an activist artist. Titled The Spear, the painting was of former president Jacob Zuma painted as Lenin, but with his penis exposed in a piece that referenced the parable of the Naked Emperor, the cautionary tale of what happens to leaders whose followers are too scared to tell them the truth.

Murray’s first works were painted during the Struggle against apartheid as part of the cultural resistance and he hadn’t stopped resisting, especially as the governing ANC descended into corruption. The art review caused the first Twitter storms and I was targeted as the hive of hate swarmed. Cabinet ministers, party leaders and one of the president’s wives marched against the painting. I have forgotten most of the hate, but this sticks.

“You’re single. Do you go to sleep with the painting,” said one parody account on Twitter pretending to be one of South Africa’s richest men, Patrice Motsepe. That made me feel ill, but I didn’t know the words yet to explain why. There was more. A local activist I know tweeted that I had told him there would be no edition of City Press the next day. There was mayhem. I was scared. People knew where I lived. We didn’t have the language to describe digital misinformation or disinformation.

I pulled the digital version of the painting off the Net after the First Lady personally burnt copies of the print edition.

I have a love and hate relationship with Twitter that has continued for 10 years. As a journalist, it has been revelatory to learn to micro-report, to live blog, to carve an opinion in the constraints of 140 characters. I enjoy this as it has freed me from the strictures of long blocks of text or to have to wait until a commercially ordained deadline to break news or to influence opinion.

In this, I have experienced Twitter as a liberating tool and a democratising one. While the platform is obviously an innovation meant to commercialise and to eventually make a fortune, the new media market means that access is free except for my data costs. My world’s expanded with social media because I can read up about the politics of Azerbaijan as easily as I can about local news.

I enjoyed Twitter. Until it turned on me.

Bell Pottinger strikes

One day after publishing an essay that took me months to report and which had been done with due care and consideration, I opened my feed to find distorted images of myself as a gargoyle and a mad elf starting back at me. “What the fuck,” I thought and scrolled, alarmed at the images of myself jumping out at me.

The essay had been an in-depth look at what we call “State Capture” in South Africa, a sophisticated corruption where policy and positions across the state are commandeered by powerful patronage networks. In this case, the patrons were the Gupta family, an Indian immigrant family who had befriended Zuma and then proceeded to enrich themselves spectacularly. Zuma had fired a highly regarded finance minister, ostensibly at their instruction, and I had pieced together the story.

I had heard via the family and other grapevines that a group of journalists who had written about the Guptas were under surveillance and were a target, but I had given it little thought.

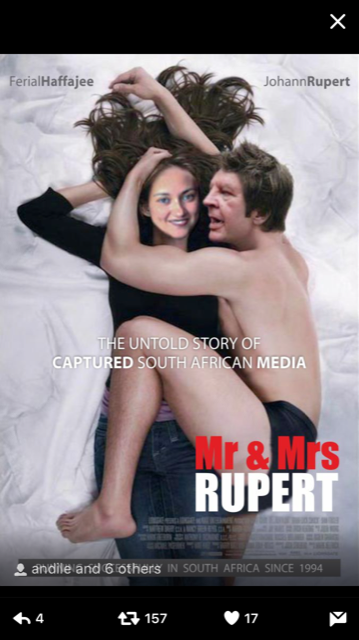

Now, this. The images bombarded Twitter for weeks. After the first distortions, they morphed into images of more destructive hate. There was an entire set of memes with me either on the lap of, in the bed of and on the desk of the billionaire Johann Rupert, who was the face of the family’s campaign by the global PR company Bell Pottinger. Later, I was photoshopped on to a barely clothed dancer; then I was a busty cheerleader wearing a barely-there costume; then I was a dog being walked by Rupert and a cow being milked by him. A dog, a cow, a prostitute — the nasty purveyors of online hate could not get more stereotypically sexist.

It’s clear now that Bell Pottinger, the global PR company, designed the campaign in the same way they had designed black ops in countries such as Iraq and elsewhere. I think Bell Pottinger executed the online campaign by using click farms and designers in India from where the Guptas ran some operations. A group of us is suing Bell Pottinger (or its insurance company as the PR giant went bankrupt) for this campaign and the jury’s out on whether we will succeed.

I am Julius Malema’s roadkill

I’m roadkill, not an equal of Malema’s and other trolling armies, because they have impacted on me.

The images of the Bell Pottinger campaign, the words of Piet and of Malema’s trolling army fill me with shame. Why is this? I have asked myself so many times how this digital misogyny impacted as hard as it did, shaming me and causing me to hide the images and to hide from them and to feel like I had to explain them. I am yet to find a proper answer, except that I have realised that when hate comes to you packaged and delivered on to your phone and into your palm, it gets into you. Our phones have become like appendages, a part of us.

The designers and purveyors of cyber-misogyny have worked this out and use online attacks to silence journalists. It is now so routine that I spend some of each day blocking hate.

Sanef’s court case is an attempt to get the judiciary to declare that this kind of hate is hate speech in terms of our Constitution and that it impacts on the founding statute’s freedom of expression provisions.

Twitter is simply useless

One day in 2018, a man was so incensed by an opinion I tweeted that he sent me a direct message in which he said I deserved a bullet to my head. This, for daring to have an opinion. The man did not bother to hide his identity as cyber-sleuths quickly worked out who he was. I reported it to Twitter and I got through the bots who take reports. He was blocked. For a time. There is no life sentence for making death threats against women on Twitter.

Twitter, Facebook and Google’s executives flood the free media conference circuit and speak the language of ending cyber-hate and online misogyny against journalists. This trend is now recognised by Unesco as a rising threat to free expression. But on the ground, I have found Twitter’s chatbots, which field first line reporting, to be singularly unhelpful. I try to report all hateful messages and all attacks. Most times I get a bot (or a poorly paid and poorly trained casual worker in one of their outsourced customer complaints teams) which or whom, in essence, tells me I have to put up and shut up when called “bitch”, “cunt”, “witch” or any of the casually flung epithets that come at us day after day.

These do not violate Twitter rules, the bot response will email me and advise me to block or to mute the hate. It’s the digital equivalent of telling women journalists like me to go and cover easier beats than investigative and political journalism that do not generate hate. That outcome, I guess, is just what the online merchants of hate want — to get us off the beat.